I have to admit that I was fairly disappointed with Alexander's piece. Gaming and writing sounds really cool, and I'm rather fond of Gee, but having recovered from the "WoW addiction" after a three-year bender, I really don't see how this could be any more than a specialized pedagogy.

First, I'd like to declaim a few assumptions that Alexander makes:

1) 50% of college students play video games (36). This is probably true. However, Alexander focuses in on WoW as the basis for his article, and I would say that the number of college students who have played WoW is about 25% of the 50% of gaming college students; in fact, I'd say only about 5% of college students are the type of serious WoW players that "Mike and Matt" are. Really.

2) People who play WoW or other MMORPGs utilize five different literacies--literacy reflectivity, trans-literacies, collaborative writing, multicultural literacies, and critical literacies (45). Not IMHO--that's netspeek for no fucking way. Having been a player like Mike and Matt, I recognize all five of these literacies and admit that some players do use most or all of them. However, Mike and Matt use all of these literacies because they are the leaders of a guild; most members of a guild do not, or at least do not use many of them. Furthermore, very few players are actually members of guilds that utilize these literacies; most players are not active guild raiders like Mike and Matt.

3) People who play WoW are collaborative (41-2). This one's kinda implied, but it's there nonetheless, and is only true to a limited extent. Again, Mike and Matt are not typical; by now the process of "levelling up" to 80 (maximum level, where all the content that Mike and Matt engage in is located) is largely done through "solo play." The process of levelling up involves repetition of quests that are themselves quite repetitive (kill 8 monsters, turn in quest, repeat for three months), and there are very few rewards for collaborative play--unfortunately, until very high levels, collaborative play is too time-consuming (and requires too much organizaiton or coordination) to be practical for most players. This is ironic, considering that most people join with the intent of playing with other people; however, in my experience, friends who buy the game together often find that they cannot play at the same time, or one player levels-up too far ahead for the other player to catch up, or one of any other myriad of barriers crops up to prevent collaborative play. True collaborative play does occur at max level, if the player commits to a raiding guild, and if that guild makes a serious committment in time, energy, and patience to actually killing the big bosses.

I could make many more points, but this is enough for the sake of some semblance of brevity. Anyway, my point is that Alexander spills a great deal of ink to outline the literacies that Mike and Matt demonstrate--which are great--but are unrealistic when applied to most student gamers, or even most WoW players.

Of course, I missed Alexander's most basic assumption--my bad: "incorporating a strong consideration of gaming into composition courses may not only enliven writing instruction for many of our students, but also transform our approach to literacy" (37). I'll agree to the last point--Alexander wrings a great deal out of Mike and Matt's interactions--but due to my comments on assumption #1, I don't believe that working gaming/MMOs into our syllabi is going to help most students; there's just too few students who play MMOs or WoW, fewer that play at Mike and Matt's level, and a plethora of students who will actively resist such activities. Also, again in my experience, most players are loathe to admit to their classmates that they're gamers--there's too much of a social stigma associated with game-playing (yeah, I know that we love to challenge those types of cultural taboos, but promoting acceptance of gamers is down the list on the causes I care about--there's bigger issues to tackle). Furthermore, it'd be too problematic to try to arrange; I know Shawn LameBull likes to hold the occasional class session in Mulgore, but many students simply don't have access to gaming computers or accounts, and some students are always excluded.

So, I guess I'm probably the black sheep in that I just don't see the value of using video games, especially WoW, in FYC. I could see Alexander's approach as being a great proposal for a new course (Engl 4XX/5XX--Video Games and Composition), which would consist of students who are very interested in studying gaming, literacy, and writing, but I stand firm that it would be an absolute disaster for a FYC course.

Monday, March 29, 2010

Sunday, March 21, 2010

Bitch Shop!

I decided to take a page outta Tim's blog and visit Bitch and BUST for a look at what all of Helmbrecht & Love's fuss was about, and the image above was, literally, the first thing I saw on Bitch's homepage. Considering that H & L point out that shopping and consumerism are part of both magazines (why are H & L calling them zines? Both identify as magazines, and appear far different in form and content than zines), I felt that the title and above image were an appropriate criticism of 3rd-wave feminism (160). More on this in a moment, but first a personal declaration (again responding to Tim's need to identify his own context vis a vis feminism).

I actually do consider myself a "good gauge of this kind of thing"; as I'm sure everyone has heard me say ad nauseum, I grew up in a counter-cultural mix of 3rd-wave feminism and queer culture, with an incredible dose of what H&L (snobbishly) call "the casual and hedonistic approach to sexuality" thrown in for good measure. And I consider myself a part of these movements, so the following criticisms and analyses (as well as the previous) are offered from love.

So Barbara offered us a challenge in an email from last Friday by asking us to "tease out what the third wave is all about," and it was with that in mind that I approached H&L's article. I came up with some key features of 3rd-wave feminism, fished out of examples from H&L:

- A focus on agency and individualism: as H&L note, both magazines feature articles that encourage women to make their own choices about their lives, especially in areas that have been traditionally verboten to feminists (such as sewing and cooking, shopping, blunt expression of sexuality, etc.) (156-8, et. al.)

- A focus on the individual rather than the institutional: this one kinda overlaps with the last one, but is more marked by the absence of the institutional criticism that was a big part of 1st and 2nd wave feminism. H&L point this out when analyzing one article's stance on cooking and cleaning, stating that "this reader fails to acknowledge the social conventions and oppressive institutions that compel women to cook for a household in the first place" (158). 3rd-wave feminists just tend to overlook, avoid, ignore, or sometimes refuse to discuss institutional structures of oppression, possibly as a reaction to 2nd-wave's focus on equalizing institutional opportunities.

- "Domesticity is uber-cool": H&L seem to view this aspect of 3rd-wave feminism with at least suspicion (if not disgust), but note that Bitch and BUST (especially) both seem to promote housekeeping, cooking, crafting, fashion, shopping, and other activities associated with patriarchal women's roles (160). I would go even further than H&L do to assert that the fashionably-domestic 3rd-wave feminist extends even to homemakers and stay-at-home moms; many of the "hardcore" lesbian feminists I grew up with--women who definitely epitomized the anger, intellect, and sass that is exemplified in Bitch (and particularly praised by H&L)--are now happy, married, heterosexual, domestic moms. Assimilation? I don't think so--it stays tied into the agency and individualism of the movement.

- Appropriation of derogatory terms: H&L also mention the trend, most notably in the name of the magazine, towards taking back terms like "bitch" (as queer-studies has done with "queer") and turning them into a positive ethos (161-2). 3rd-wave feminism is rampant with the flipping of traditional epithets aimed at women, and probably the most successful and mainstreamed example of this is the contemporary use of the word "douchebag" (or more commonly, "douche"). Formerly a term, originally associated with the Italian-American street lexicon, to refer to women, it is now used so frequently in the popular lexicon that it can be heard weekly or daily on South Park, The Daily Show, and even the nightly news; however, its contemporary usage is limited strictly to men. Its mainstream usage is quite recent (only the past five years or so), but in my experience has been in use by 3rd-wave feminists for at least fifteen years.

- One important one that I didn't find much example of in H&L is sexuality. The closest example is when H&L criticize a BUST editor, Tracie Egan, for promoting a "casual and hedonistic approach to sexuality" that "is audacious sexuality" (157). H&L conclude that "the interruption of mainstream discourses on women's sexuality is significant and encouraging, yet this sassy and sexy ethos is not necessarily smart." The problem is that H&L overlook this as a key feature of 3rd-wave feminism--the ability to bluntly express one's personal sexuality; while H&L acknowledge the agency in Egan's article, they characterize Egan's response as young, foolish, and problematic for teachers. In other words, H&L dismiss Egan because of her apparent unconcern for STDs, and in doing so they dismiss the ethos of her sexuality. For 3rd-wave feminism, which is mostly dominated by young women, sexuality is something that should be above criticism. While 1st and 2nd-wave feminism advances womens' sexuality significantly, these movements still left plenty of room to criticize some women for their sexuality; for example, in Parental Advisory: Explicit Lyrics, George Carlin comically remarks that "I also happen to like it when feminists attack these fatass housewives who think there's nothing more to life [than having a baby] every nine months." If even George Carlin is noticing feminists attacking other women for their sexuality (which does definitely include the reproductive phase of womens' lives), it seems clear that women's sexuality was not above reproach in earlier feminist movements. Again, 3rd-wave feminism seems to take many reactionary stances to 2nd-wave feminism, and one of those positions is to value sexuality as a topic where criticism tends to be taboo.

I've covered a lot of shit in this blog, and I think I've already written way more than I needed to. Hopefully this will make for good discussion on Tuesday.

Monday, March 8, 2010

Sarah Palin, Gameplaying, and the Three-Legged Fool

In the interest of irony (even the abridged Ong was a long read :D ), I've decided to make my comments on this week's readings fairly brief. Of course, this is not to say that there ain't a lot to say about them, but rather to provide some interesting talking points for Tuesday.

First, I've always been intrigued by Ong's Orality and Literacy, and in fact I've found bits of it quite useful in explaining sentence structure to Engl 102 and GenEd 302 groups--for students who often write the way they speak (which occurs often, regardless of whether they come from a culture of orality/secondary orality), the "additive vs. subordinative", the "aggregative vs. analytical", and the "copious" sections make for quick, easy, and helpful reading (I sometimes summarize) when discussing things like redundancy, flow, and clauses (37-41). Often, my favorite examples of redundant, aggregative or formulaic speech/writing come from Sarah Palin--consider her response to David Letterman's description of her as having a "slutty flight attendant" look:

Next, Ong's comments about "the dozens" (Ong's description always makes me chuckle a bit--so academic!) and his description of oral culture as being close to the "human lifeworld" brought to mind another game that parallels the agonistic features of "the dozens" while maintaining that connection to the world around us (42-44). Back in Olympia, people on the street play a game where two or more participants compete to demonstrate their awareness of their surroundings. When one participant sees someone strange, ugly, stupid, etc., they will say to their companion, "Your team." The point of the game is to associate the odd-acting person with their companion, and is obviously highly judgemental and often quite crude. However, the game serves another purpose, one well suited to life on the street: by pointing out unusual people to their companions, participants remind each other to be mindful of their surroundings and to maintain a keen awareness of the people around them. While I am now a graduate student in one of the safest suburbs in all of Washington, I still teach my friends the game and continue it because, aside from amusement, it teaches a valuable lesson.

Finally, what stuck most in my mind about Barbara's piece is her description of the three (+1) trends in composition (W337). While Barbara describes herself as having "one foot" in two different "camps," I left the passage feeling like a fool stumbling through a three-legged race; I've got one leg in acculturation, one in hybrid discourse (the dominant one, of course), and one in multimedia composition, and I feel as if it won't be long before I trip. While I dislike the acculturation perspective (reminds me too much of the Borg from Star Trek--"You will be assimilated. Your cultural and biological distinctiveness will be added to our own."), I have to respect that students will need to be able to produce traditional academic discourse upon demand simply for their own survival. So now I've got to figure out how to run with this extra leg without letting it trip me up.

First, I've always been intrigued by Ong's Orality and Literacy, and in fact I've found bits of it quite useful in explaining sentence structure to Engl 102 and GenEd 302 groups--for students who often write the way they speak (which occurs often, regardless of whether they come from a culture of orality/secondary orality), the "additive vs. subordinative", the "aggregative vs. analytical", and the "copious" sections make for quick, easy, and helpful reading (I sometimes summarize) when discussing things like redundancy, flow, and clauses (37-41). Often, my favorite examples of redundant, aggregative or formulaic speech/writing come from Sarah Palin--consider her response to David Letterman's description of her as having a "slutty flight attendant" look:

"Pretty pathetic, good old David Letterman, that old David Letterman, what a commentary there ... very sad not to recognize what this trip was all about [...] Just doing some good things here for some good people in New York... such a distortion." [my italics]Notice the repetition and use of adjectives; granted, this is from speech, not writing, but in the press release for her resignation (which used to be on Alaska's official website), written by Palin herself, the same features keep popping up.

Next, Ong's comments about "the dozens" (Ong's description always makes me chuckle a bit--so academic!) and his description of oral culture as being close to the "human lifeworld" brought to mind another game that parallels the agonistic features of "the dozens" while maintaining that connection to the world around us (42-44). Back in Olympia, people on the street play a game where two or more participants compete to demonstrate their awareness of their surroundings. When one participant sees someone strange, ugly, stupid, etc., they will say to their companion, "Your team." The point of the game is to associate the odd-acting person with their companion, and is obviously highly judgemental and often quite crude. However, the game serves another purpose, one well suited to life on the street: by pointing out unusual people to their companions, participants remind each other to be mindful of their surroundings and to maintain a keen awareness of the people around them. While I am now a graduate student in one of the safest suburbs in all of Washington, I still teach my friends the game and continue it because, aside from amusement, it teaches a valuable lesson.

Finally, what stuck most in my mind about Barbara's piece is her description of the three (+1) trends in composition (W337). While Barbara describes herself as having "one foot" in two different "camps," I left the passage feeling like a fool stumbling through a three-legged race; I've got one leg in acculturation, one in hybrid discourse (the dominant one, of course), and one in multimedia composition, and I feel as if it won't be long before I trip. While I dislike the acculturation perspective (reminds me too much of the Borg from Star Trek--"You will be assimilated. Your cultural and biological distinctiveness will be added to our own."), I have to respect that students will need to be able to produce traditional academic discourse upon demand simply for their own survival. So now I've got to figure out how to run with this extra leg without letting it trip me up.

Monday, February 15, 2010

First of all, I was about to post this on Pam's entry as a comment, but then I realized that it's longer than most abstracts I've read--nevermind blog comments--so I decided to post it on my own blog instead. Also, I must apologize to Anwr for posting this so late in the night; part of my tardiness is due to the fact that I struggled with the Gee article for some time (more on this later), and part of it is due to the fact that I literally live underground (and therefore don't usually notice whether the sun is up or not any more than I notice what time it is). Anyway, the first chunk is in response to Pam's blog:

In response to your question about AA students being better prepared for online discourse, I have to agree. From what I've read from Barbara's reading, AA students (at least those mentioned in the article, which I might expand to native speakers of AAE) seem better prepared to adapting to different Discourses (using Gee's definition), if for no other reason than the variety of different Discourses to which they must adapt to survive and because of the public nature of their primary Discourses.

The UM students, on the other hand, seemed very unable to deal with online discourses as potentially public conversations; I would go so far as to attribute this to WMC expectations of privacy, even within school settings (which could be because of any number of factors). The fact that they made such a concerted effort to maintain privacy--ostensibly to foster personal connections with the students they tutored, which is also noteworthy considering that they maintained this even after hearing about how their introductory emails were subjected to public performances--might reveal some hints about their own discursive, racial, and/or cultural values.

From my experience, I notice that I tend to treat any of my own discourse as a public performance; in both street culture and WMC culture, I learned early that anything I said or did could, and often did, become public very quickly; signifying and performing became survival tools.

The big question, I think, is how we can harness these public/private discursive perspectives within the composition classroom: how do we encourage WMC students to see online discourses as public (or any discourse as public) without shutting them down, and how can we harness native AAE students' (or students from other discursive backgrounds who view discourses as public) perspective on public discourses in the classroom?

Also, Pearce asked, on Malcom's blog, what makes a "dance" (etc.) more authentic than another. I'm going to be a pain in the ass and answer your question, Pearce. In my experience, "recognition work" is (in varying degrees of severity) a relativistic attempt at establishing authenticity in order to survive in that discourse community. What makes one performance more authentic than another is the verbal and non-verbal discursive cues that compose a particular performance, and how well they conform to the discourse of that community.

For example, if I'm having a cigarette outside a place (restaurant, club, park, tunnel, etc.) that carries some possession within a particular community, and a member of that community is also lighting up and decided to make conversation, I have to put on a performance to demonstrate that I belong there.

Let me give a more specific example: I'm outside The Roxy (a diner in Portland, Oregon that serves the Stark Street subculture), and I'm having a smoke next to a white guy wearing a military trenchcoat and jeans, with short greasy hair and a ring through his nose. I'm wearing the same hoodie and jeans you often see me wearing in class. He asks for a light, and then asks me "How's it going?" My performance in the following conversation will be judged for authenticity as to how well I belong to Portland street culture, whether I display markers as a member or ally of queer culture, and how much knowledge I can portray of the local community. In other words, I'm being judged relative to *his* experience of that community, whether it's as an outsider (unlikely), a long-standing member with many memories of other community members and subcultural locations, or as an initiate (as Gee calls it, "being-or-becoming-a" member of that community). He might judge my performance as demonstration that I am: a) a poser--someone who does not belong there, b) a fellow initiate, or c) a veteran member of that community, who he may still view as either a threat or a role model--depending on his own position relative to that discursive/subcultural community.

My example is just another way of describing the "dance" that Gee portrays between a "real Indian" and another "real Indian," and may involve a certain amount of "razzing," signifying, or self-expression (another example is the amount of "dancing" that you and I do in our in-class and online arguments!). But whatever the context, it's always going to be a dance; that is, it will always be relative to the experiences of those engaged in the dance (which will not always, or even often, be between only two people; for example, picture the Roxy example with an attractive young girl present--perhaps one who displays/performs many cues to veteran membership in the community).

It's taken me a long time to write all this because Gee's article was, on many levels, quite troubling for me. While Barbara's chapter was very helpful from a pedagogical perspective--especially in grappling with issues of intercultural and intertechnological communication (the UM tutors had far more access and experience with computers, whereas the Detroit students were constantly surrounded by officials who were monitoring "the first email sent to a Detroit high school"), Gee's article particularly challenged me because of how it dealt with issues of authenticity, especially relating to "real Indians" and differences between Native discursive practices and WMC practices.

While I definitely do not feel or see myself as a "real Indian," coming from a (passing) white working class/lower middle class family, many of the discursive characteristics he describes--especially about the "crisis in identity" experienced by Athabaskan Natives in writing those damned self-portrayal, self-display essays demanded by WMC educational systems from K-PhD--click with my own personal and home discourses; in fact, one of the main struggles I've had with my education is in creating any sort of self-display (I'm still learning to adapt). This is further complicated by my mixedblood identity, which includes a Native identity, having grown up a 1/2 mile from the Rez; in fact, throughout my life my closest friends and the people I find it easiest to bond with have also been mixedblood Natives--this may be due to the recognition that Gee remarks on (24) or it could be due to the fact that I grew up in a community with a higher-than-average percentage of Native and mixedblood people (I'm just not sure). So reading Gee was particularly difficult for me because it lead me to "dance" with my own identities just to write a simple blog.

Anyway, after all that, my question/hypothesis is: Do you think that the ability to do "recognition work," as Gee calls it, or adaptation to a variety of distinct discursive communities (as I call it), is affected by one's need to survive, and therefore is often more pronounced in those who come from communities where the need to survive and succeed is greater? Also, don't forget my question about how to harness these differences in the classroom.

In response to your question about AA students being better prepared for online discourse, I have to agree. From what I've read from Barbara's reading, AA students (at least those mentioned in the article, which I might expand to native speakers of AAE) seem better prepared to adapting to different Discourses (using Gee's definition), if for no other reason than the variety of different Discourses to which they must adapt to survive and because of the public nature of their primary Discourses.

The UM students, on the other hand, seemed very unable to deal with online discourses as potentially public conversations; I would go so far as to attribute this to WMC expectations of privacy, even within school settings (which could be because of any number of factors). The fact that they made such a concerted effort to maintain privacy--ostensibly to foster personal connections with the students they tutored, which is also noteworthy considering that they maintained this even after hearing about how their introductory emails were subjected to public performances--might reveal some hints about their own discursive, racial, and/or cultural values.

From my experience, I notice that I tend to treat any of my own discourse as a public performance; in both street culture and WMC culture, I learned early that anything I said or did could, and often did, become public very quickly; signifying and performing became survival tools.

The big question, I think, is how we can harness these public/private discursive perspectives within the composition classroom: how do we encourage WMC students to see online discourses as public (or any discourse as public) without shutting them down, and how can we harness native AAE students' (or students from other discursive backgrounds who view discourses as public) perspective on public discourses in the classroom?

Also, Pearce asked, on Malcom's blog, what makes a "dance" (etc.) more authentic than another. I'm going to be a pain in the ass and answer your question, Pearce. In my experience, "recognition work" is (in varying degrees of severity) a relativistic attempt at establishing authenticity in order to survive in that discourse community. What makes one performance more authentic than another is the verbal and non-verbal discursive cues that compose a particular performance, and how well they conform to the discourse of that community.

For example, if I'm having a cigarette outside a place (restaurant, club, park, tunnel, etc.) that carries some possession within a particular community, and a member of that community is also lighting up and decided to make conversation, I have to put on a performance to demonstrate that I belong there.

Let me give a more specific example: I'm outside The Roxy (a diner in Portland, Oregon that serves the Stark Street subculture), and I'm having a smoke next to a white guy wearing a military trenchcoat and jeans, with short greasy hair and a ring through his nose. I'm wearing the same hoodie and jeans you often see me wearing in class. He asks for a light, and then asks me "How's it going?" My performance in the following conversation will be judged for authenticity as to how well I belong to Portland street culture, whether I display markers as a member or ally of queer culture, and how much knowledge I can portray of the local community. In other words, I'm being judged relative to *his* experience of that community, whether it's as an outsider (unlikely), a long-standing member with many memories of other community members and subcultural locations, or as an initiate (as Gee calls it, "being-or-becoming-a" member of that community). He might judge my performance as demonstration that I am: a) a poser--someone who does not belong there, b) a fellow initiate, or c) a veteran member of that community, who he may still view as either a threat or a role model--depending on his own position relative to that discursive/subcultural community.

My example is just another way of describing the "dance" that Gee portrays between a "real Indian" and another "real Indian," and may involve a certain amount of "razzing," signifying, or self-expression (another example is the amount of "dancing" that you and I do in our in-class and online arguments!). But whatever the context, it's always going to be a dance; that is, it will always be relative to the experiences of those engaged in the dance (which will not always, or even often, be between only two people; for example, picture the Roxy example with an attractive young girl present--perhaps one who displays/performs many cues to veteran membership in the community).

It's taken me a long time to write all this because Gee's article was, on many levels, quite troubling for me. While Barbara's chapter was very helpful from a pedagogical perspective--especially in grappling with issues of intercultural and intertechnological communication (the UM tutors had far more access and experience with computers, whereas the Detroit students were constantly surrounded by officials who were monitoring "the first email sent to a Detroit high school"), Gee's article particularly challenged me because of how it dealt with issues of authenticity, especially relating to "real Indians" and differences between Native discursive practices and WMC practices.

While I definitely do not feel or see myself as a "real Indian," coming from a (passing) white working class/lower middle class family, many of the discursive characteristics he describes--especially about the "crisis in identity" experienced by Athabaskan Natives in writing those damned self-portrayal, self-display essays demanded by WMC educational systems from K-PhD--click with my own personal and home discourses; in fact, one of the main struggles I've had with my education is in creating any sort of self-display (I'm still learning to adapt). This is further complicated by my mixedblood identity, which includes a Native identity, having grown up a 1/2 mile from the Rez; in fact, throughout my life my closest friends and the people I find it easiest to bond with have also been mixedblood Natives--this may be due to the recognition that Gee remarks on (24) or it could be due to the fact that I grew up in a community with a higher-than-average percentage of Native and mixedblood people (I'm just not sure). So reading Gee was particularly difficult for me because it lead me to "dance" with my own identities just to write a simple blog.

Anyway, after all that, my question/hypothesis is: Do you think that the ability to do "recognition work," as Gee calls it, or adaptation to a variety of distinct discursive communities (as I call it), is affected by one's need to survive, and therefore is often more pronounced in those who come from communities where the need to survive and succeed is greater? Also, don't forget my question about how to harness these differences in the classroom.

Sunday, February 7, 2010

Technological Intent

I've got to disagree with Pearce when he argues that technologies are not neutral; while Pam makes a good point about technologies having limitations, having been created with specific purposes in mind, these positions ignore the fact that technologies are as dynamic and adaptive as those who wield them. There is always an ongoing relationship between the tool and the technician; Audre Lourde's statement that "the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house" sounds fine in abstract, but every time I build a fire (technology) in my fireplace, I watch it with care to make sure that it does not burn my house down. In this case, my relationship to the fire is as cautious and distrustful as Pearce's attitude toward technology. But on the other hand, I'm far more certain and comfortable with fire when it's used in a different context--for example, when it is combusting gasoline in my car's engine so that I can make it to class on time when I'm running late. Gee is correct in asserting that the context of a technology is the only place where it has any effects; in other words, the technology only exists when it is put to use (Gee 21). What are the effects, good or bad, of the ballista? Virtually none; we don't use that technology anymore.

To elaborate further on the adaptive relationship between people and technology, consider Pam's example that "I can't print out this blog from my microwave": while this might be literally true, microwave technology can be adapted to allow my cell phone to display her blog, and can even be adapted to allow my 'puter to print her blog to my wireless printer. True, the tools themselves have limitations--a microwave oven is a far different tool than a printer or personal computer--but they only represent particular technologies, which are themselves abstract knowledges rather than physical objects that only manifest in tools created for specific contexts (this too is a mistake that Gee makes in explaining how television can have different contexts--he equates technology with tools). A more pertinent distinction is that between language and words; as signs, words may be tools, but it is only through their use (technological context) that they become a language.

So while technologies may originally be created to make tools that have a "bad" purpose, that relationship between tool and technician allows for adaptation by the technician. For example, while the technology of the blog may have originally been created for the purpose of allowing angst-filled teenagers to rant and create some of the world's worst poetry (at least, that's the only original purpose that I can discern), they also allow for the kind of interaction and discussion that Monroe argues is valuable to our pedagogy (Monroe 112). By hijacking these technologies for use in teaching, we adapt the technology to a new context that furthers a different purpose than its original intent. Technology created for a "bad" purpose does not suffer from some kind of technological original sin; it morphs and changes its character and virtues depending on the context in which it is put to use. The only values that it carries are those that we assign to it.

Moving on, I have a few (somewhat) unrelated thoughts about home literacies. While Gee examines the uses of literacies in pre-4th grade children, and Monroe examines some excellent uses of tween literacies, I--as a college instructor working with students well beyond these ages (and possibly already damaged by the 4th grade slump, the racial/socioeconomic gap in test scores, or who have just been chewed up and smacked around by the American K-12 educational system and other factors)--wonder how I can use students' home literacies to help them survive and succeed in the university. While I always remind my students that one of my core pedagogical assumptions is that they bring a plethora of distinct literacies and knowledges to class with them, what I struggle with is how to integrate and share these treasures with their classmates in the course. While I feel as if I've had some success in using some of these abilities in the classroom, I feel as if there's so much more I can--and need--to do to utilize their home literacies, and especially how I can encourage them to use these literacies and discourses in conjunction with academic discourse when they may have already been trained or discouraged from doing so by their previous educational experiences.

To elaborate further on the adaptive relationship between people and technology, consider Pam's example that "I can't print out this blog from my microwave": while this might be literally true, microwave technology can be adapted to allow my cell phone to display her blog, and can even be adapted to allow my 'puter to print her blog to my wireless printer. True, the tools themselves have limitations--a microwave oven is a far different tool than a printer or personal computer--but they only represent particular technologies, which are themselves abstract knowledges rather than physical objects that only manifest in tools created for specific contexts (this too is a mistake that Gee makes in explaining how television can have different contexts--he equates technology with tools). A more pertinent distinction is that between language and words; as signs, words may be tools, but it is only through their use (technological context) that they become a language.

So while technologies may originally be created to make tools that have a "bad" purpose, that relationship between tool and technician allows for adaptation by the technician. For example, while the technology of the blog may have originally been created for the purpose of allowing angst-filled teenagers to rant and create some of the world's worst poetry (at least, that's the only original purpose that I can discern), they also allow for the kind of interaction and discussion that Monroe argues is valuable to our pedagogy (Monroe 112). By hijacking these technologies for use in teaching, we adapt the technology to a new context that furthers a different purpose than its original intent. Technology created for a "bad" purpose does not suffer from some kind of technological original sin; it morphs and changes its character and virtues depending on the context in which it is put to use. The only values that it carries are those that we assign to it.

Moving on, I have a few (somewhat) unrelated thoughts about home literacies. While Gee examines the uses of literacies in pre-4th grade children, and Monroe examines some excellent uses of tween literacies, I--as a college instructor working with students well beyond these ages (and possibly already damaged by the 4th grade slump, the racial/socioeconomic gap in test scores, or who have just been chewed up and smacked around by the American K-12 educational system and other factors)--wonder how I can use students' home literacies to help them survive and succeed in the university. While I always remind my students that one of my core pedagogical assumptions is that they bring a plethora of distinct literacies and knowledges to class with them, what I struggle with is how to integrate and share these treasures with their classmates in the course. While I feel as if I've had some success in using some of these abilities in the classroom, I feel as if there's so much more I can--and need--to do to utilize their home literacies, and especially how I can encourage them to use these literacies and discourses in conjunction with academic discourse when they may have already been trained or discouraged from doing so by their previous educational experiences.

Sunday, January 31, 2010

Drowning in metaphors

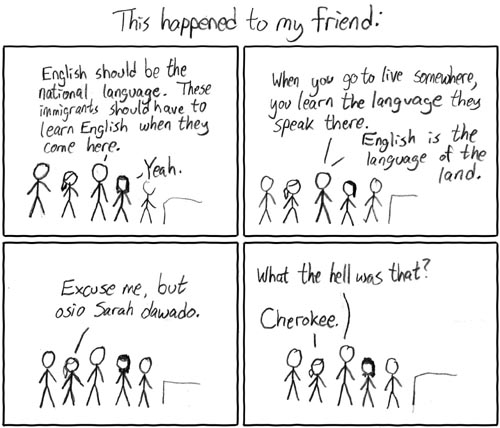

This comic has been bumping around in my head during our discussions, and it's wonderfully convenient that Bizzell mentions Scott Lyons's piece on Rhetorical Sovereignty--otherwise, it might seem hard to connect it to our readings. I find it useful because not only can it compare traditional academic discourse to the mixing, remixing, patchwriting, and/or codemeshing that alternative discourses encompass, but it also demonstrates the difficulty in using hybrid discourses while still communicating with fellow scholars. For example, in referencing the Williamson essay, Bizzell notes that "Williamson's reviewers react to this structure by finding it hard to connect the themes he broaches," and that "there is ample evidence that the form disturbs them" (Bizzell 6). I'm sure that if another panel was to be drawn for this comic, the pro-national-language figure would have a similar reaction, whether or not he concedes the point.

A few things disturb me about Bizzell's argument though. First, she argues that "the best evidence" she can find for using hybrid discourses come from "powerful white male scholars" who employ these discourses in their scholarly work. From this admission, it would seem as if the only way hybrid discourses could be legitimized is by their anointment from the same privileged white men who legitimize traditional academic discourse. This is problematic because it places power in the hands of those whose resistance to hybrid discourses and promotion of a "correct" grapholect created the need for other discourses in the first place. We--as proponents of hybrid discourses--don't need a Jake Sully to rescue us from linguistic imperialism (of course, I see the irony, as a white male, in saying this).

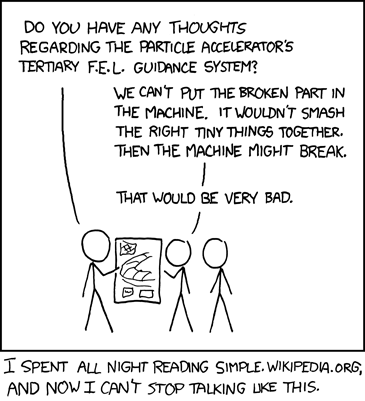

Also, Bizzell is only able to draw on one example to illustrate her point. While this may be sufficient for a short publication, where it might be better to explore one example in depth rather than shallowly reference several or many other examples, I'd like to see other examples outside of English studies. Finally, the focus of her argument and examples seems to be centered on the humanities--which is great, except it would also be even better if she could provide examples or make proposals for hybrid discourses in the sciences. Perhaps one humorous example might look like this:

This is why I like Royster's assumption that academic discourse is plural--if we're to be trapped within dichotomies of traditional/alternative discourses, then we simply fall into the same white/everyone else pattern that allows linguistic imperialism to flourish--same dichotomy, different format (Royster 25). While, for the most part, Royster's nautical metaphors make me feel more than a bit seasick, I do agree in moving away from invasive and imperialistic patterns (Royster 26).

As a final note on pedagogy, I completely agree with Royster in the need to recognize classrooms as public, not private, spaces (Royster 27-28). And while this does make the writing classroom a high-risk place, it also provides commensurate rewards; by making students' writing visible and public, through blogs, multimedia presentations, or even put on display on the document camera, they may enjoy the same delight that all writers feel when their work is--in some form--published and accepted or applauded by their peers.

Sunday, January 24, 2010

Hybrid Discourse, Patchwriting, Codemeshing, Remixin'

Patricia Bizzell's treatises on the new developments in academic discourse expand upon the idea of "traditional academic discourse" to include other rhetorics in the process of academic research. In both "Basic Writing and the Issue of Correctness, or, What to do with 'Mixed Forms of Academic Discourse" and "Hybrid Academic Discourses: What, Why, How," Bizzell directly challenges the notion of "correctness," or that there can be a static form of acceptable academic discourse. While in "Hybrid Academic Discourses" Bizzell acknowledges "that a sort of traditional academic discourse can be defined," she also recognizes that "traditional academic discourse must share the field with new forms of discourse that are clearly doing serious intellectual work." Although Bizzell targets the study of Basic Writing for her original challenge, her assertion that other discourses have validity within the ivory tower of academia extends beyond those students who she targets as "hybrid" students--those outside the privileged race, class, and gender of yesterday's university.

Bizzell is likely correct in challenging her own term, "hybrid," to describe these new discourses; in problematizing "hybrid" as "too abstract and too concrete," Bizzell recognizes that the term itself is too often describing the person and not the discourse. While I'm quite fond of "hybrid" as a term to explain and discuss identity--being of mixed race, ethnicity, religion, sexuality, and recently class (higher education has done a terrific job of allowing me to pass for middle-class), among other identities, it is exceptionally suited to allow me to defy binaries--I must agree with Bizzell that something else is needed to discuss shifting discourses in academia and other realms of power.

Some of the other terms I've read in academic literature for this change in lexicon and formality are "patchwriting" and "codemeshing" (the latter of which I have far more tolerance for, since linguistically it seems to get closer to the definition of new discourses). While they may avoid some of the pitfalls of the taxonomically-prone "hybrid," they still seem to lack both a relatable definition and a popular or current appeal. In other words, they're still too damned academic!

Instead, I like to think of this phenomenon of diversifying discourses as "remixing." For example, I find that much of the discussion of new discourses is similar to, the current social controversy of remixing media. While remixing is generally a term used to describe the alteration of original works of art (usually multimedia art, including songs, television, movies, internet videos, etc.) it is also perfectly appropriate to describe the growing hybridity of academese (interestingly, the discussion of hybridity in academic discourse is far more welcoming than the discourse of remixing as it applies to commercial material). Just as intrepid artists are taking commercial media and remixing it to create a new media, perhaps by adding what Stephen Colbert refers to as a "pumping k-hole groove," academics are taking traditional academic discourse and remixing it to create a new dialect that is a hybrid grapholect--one which can be read more easily as an oral or conversational discourse than as a medium that is meant to be read from a written artifact.

In my pedagogy, I intend to introduce this comparison between these two discourses of hybridity through a revealing interview from the Colbert Report in order to spark a conversation about voice, hybridity, and academic discourse (as well as acknowledging indebtedness):

Just as the interview invites viewers to consider new forms of hybrid art and media, my intention is to invite students to invent new forms of academic discourse. Academics are already changing the way intellectual work is presented, researched, and discussed--this blog is proof of that!--and so it seems quite appropriate to discuss new and/or current terms for discussion.

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

I chose this photo because I think it exemplifies my understanding of cultural contact and hybridity. The individual in the photo is composed of multiple identities, most or all of which live in a digital contact zone community of other hybrid individuals, all under the blessing--and watchful eye--of capitalism. The photo itself is taken from a conference paper on marketing to individuals/communities with hybrid identities.

Authority and its use in pedagogy comes into greater recognition in Kaplan's "Foreword: What in the World is Contrastive Rhetoric?" Like de la Vega's use of only the authoritative dialect/genre in his work, writing teachers often only recognize that which is written in SASE and authority genres. His example of a cooking recipe sonnet provides an excellent example of the problem: while it would be a wonderful example of creativity, hybridity, and possibly even parody of authority, if a student were to turn one in for a sonnet-writing assignment most poetry or literature teachers would probably be offended.

As teachers of writing, we have a choice (for now) between teaching in a monoculture (real or imagined) or doing away with some of the authority and simplicity that a monoculture offers. If we choose monoculture, we risk becoming as alienating and damaging as Ruby Payne; if we choose hybridity, then condemn ourselves to a deluge of painful questions. Perhaps 'condemn' is not the right word for those of us who delight in these new paradigms, but they're certainly not easy to answer or explain, and even Kaplan calls them "terrible questions." Of course, the reality is that monocultural, monolingual, monodialectical teaching simply won't be an option for very much longer, which makes the choice between monoculture and hybridity not really a choice at all.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)