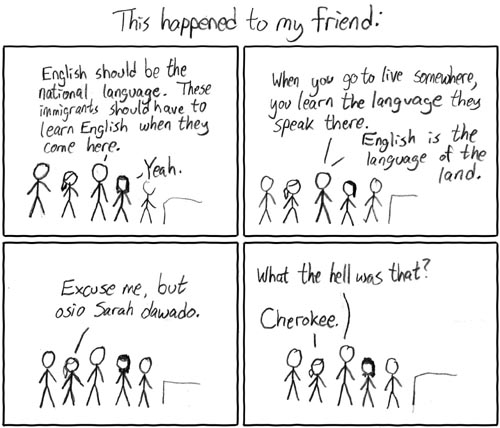

This comic has been bumping around in my head during our discussions, and it's wonderfully convenient that Bizzell mentions Scott Lyons's piece on Rhetorical Sovereignty--otherwise, it might seem hard to connect it to our readings. I find it useful because not only can it compare traditional academic discourse to the mixing, remixing, patchwriting, and/or codemeshing that alternative discourses encompass, but it also demonstrates the difficulty in using hybrid discourses while still communicating with fellow scholars. For example, in referencing the Williamson essay, Bizzell notes that "Williamson's reviewers react to this structure by finding it hard to connect the themes he broaches," and that "there is ample evidence that the form disturbs them" (Bizzell 6). I'm sure that if another panel was to be drawn for this comic, the pro-national-language figure would have a similar reaction, whether or not he concedes the point.

A few things disturb me about Bizzell's argument though. First, she argues that "the best evidence" she can find for using hybrid discourses come from "powerful white male scholars" who employ these discourses in their scholarly work. From this admission, it would seem as if the only way hybrid discourses could be legitimized is by their anointment from the same privileged white men who legitimize traditional academic discourse. This is problematic because it places power in the hands of those whose resistance to hybrid discourses and promotion of a "correct" grapholect created the need for other discourses in the first place. We--as proponents of hybrid discourses--don't need a Jake Sully to rescue us from linguistic imperialism (of course, I see the irony, as a white male, in saying this).

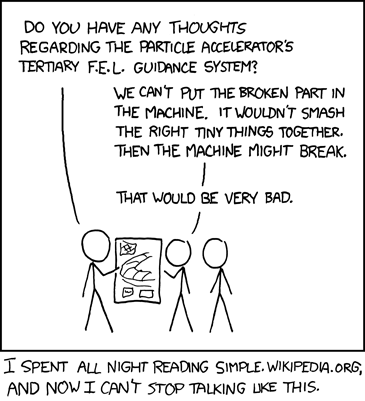

Also, Bizzell is only able to draw on one example to illustrate her point. While this may be sufficient for a short publication, where it might be better to explore one example in depth rather than shallowly reference several or many other examples, I'd like to see other examples outside of English studies. Finally, the focus of her argument and examples seems to be centered on the humanities--which is great, except it would also be even better if she could provide examples or make proposals for hybrid discourses in the sciences. Perhaps one humorous example might look like this:

This is why I like Royster's assumption that academic discourse is plural--if we're to be trapped within dichotomies of traditional/alternative discourses, then we simply fall into the same white/everyone else pattern that allows linguistic imperialism to flourish--same dichotomy, different format (Royster 25). While, for the most part, Royster's nautical metaphors make me feel more than a bit seasick, I do agree in moving away from invasive and imperialistic patterns (Royster 26).

As a final note on pedagogy, I completely agree with Royster in the need to recognize classrooms as public, not private, spaces (Royster 27-28). And while this does make the writing classroom a high-risk place, it also provides commensurate rewards; by making students' writing visible and public, through blogs, multimedia presentations, or even put on display on the document camera, they may enjoy the same delight that all writers feel when their work is--in some form--published and accepted or applauded by their peers.